Every programmer I know has at some point longingly expressed how “[they] want to work with [their] hands”. Some say they wish they were a carpenter, some want to be in the fields on a farm, some want to raise chickens, or milk cows. It is however inevitable that I either hear someone say it or agree with it at some point. Often, the sentiment is accompanied by a general dissatisfaction with the impact of the speaker’s work or profession. Maybe someone just got a particularly mind-numbing feature request, or spent several weeks arguing in meetings about several pixels of padding for text on a button on a support page in a single app.

One of the first examples that got me to notice this ongoing trend was back around the end of 2020, when a number of my friends shared and commented on a hackernews thread about someone who had responded to a request to add an RSS feed to a DBMS with the news that he had quit programming and switched to carpentry, in a particularly pithy manner (as an aside, I took a look at his woodworking shop while writing this up, and it is quite beautiful, you should definitely check it out).

Now the relevant part here isn’t necessarily this particular post or person (It seems to me that he really prefers and loves woodworking over software which is of course completely valid, and I honestly understand it in many ways), but the reactions to it, many of which were wistful among people I knew as well as among the comments online. Though there was certainly debate between commenters(see the thread linked earlier if curious). If I had to sum up the reactions, they fell into two camps. It was split between a group who mainly expressed admiration and a desire to be doing similar work, interspersed with condemnations leveled towards modern software practices and businesses, and a second group who mainly saw the flaws in modern development as being similar to those in any other job, or who thought that other jobs were even worse off. My real interest in writing this post is exploring why people – especially tech workers – seem to resonate so strongly with stories such as this one, where other tech workers leave behind their positions to return to work based in crafts, agriculture, or homesteading. This is particularly interesting to me given the seeming stability of this fascination regardless of the economic situation for tech workers (in 2020, the market was quite strong, though there’s been noted layoffs in recent years). In fact, here is another thread on reddit from a year ago referencing the same phenomenon. Another one here I've only looked through the comments of, but many discuss their desire to leave IT for farming. If you aren't a tech worker, trust me in that you will hear people say how much they want this if you are a tech worker.

ebd2’s post was just one particularly salient example, but if you’ve been online enough over the last decade or so, you’ve probably seen plenty of these kinds of posts in the same way I have, and not just from software developers or general tech workers. Across tech, it appears that many people are tired of working in offices, with computers, with meetings or emails, and want to abandon this life and start anew in more meaningful labor. In fact, over the last few years, there’s been a noted increase(see here or here) in a style of content that portrays idyllic lifestyles in times perceived as simpler, especially in short form video content. I can’t help but propose this “cottagecore” type content as deriving from the same zeitgeist. For popular examples, take a look at Nara Smith making all sorts of odd things from scratch, or at the popular but ominous ballerina farm, which inspired significant discussion over it’s formation (discussed here among other places). If this content is so wildly popular, there’s certainly some form of backlash against modernity and a desire to turn back the clock.

After hearing this desire to return to a more hands-on type of labor once again recently, I began to ask myself why it was so common. Why does everyone who sits behind a computer long to be out in the fields or workshops? Is this specific to some subgroup in tech that I happen to cross paths with regularly, or is it a broader modern ennui? To understand why I find the topic so interesting though, you’ll probably require a bit of background on me. I currently work as a researcher in the application of machine learning to problems in healthcare and genetics, but I was raised on a farm in a very rural area of Vermont. My mother’s side of the family have been farmers in the area for generations, generally growing and selling hay, as well as sheep and some amount of dairy farming. As a child on a farm, I of course helped work on the farm – throwing hay bales, carrying water buckets, shoveling massive piles of manure. I also worked in the associated side industries, like basic construction. I appreciate what I learned from this work, and the lessons were deeply valuable ones, but at the same time I would be lying if I didn’t admit that the intensity of it was a serious motivator for me to study harder than I otherwise would have and focus on technical skills, precisely so that I wouldn’t have to do physical labor anymore. I dreamed about the idea of getting paid to sit in an air conditioned office, free of clouds of dust, never having to deal with the constant little cuts and pricks from the blades of dried grass in the air of a hayloft slicing my arms over and over. Personally, I still like gardening, and there are parts of farming I enjoy quite a lot. If I lived in an area with more space, I would likely still farm as a hobby, but having your income or food supply come from it is a very different concept in terms of stress.

Considering that, I hope it makes sense as to why I find this trend puzzling. Why would people who are so comfortable, whose job was to me a lifelong goal, want to do exactly what I worked so hard to move away from? I suspect the answer is tied up in the nature of our work in the modern world, as well as in the inspection of who has been mythologized in American history. So we’ll be taking a short departure from the modern day to look into this, if you’ll excuse the seeming change in subject. In the following sections, I’ll largely focus on this from the perspective of farming in terms of verbiage and discussion, but I believe many of these psychological yearnings and trends in the American populace in relation to manual craftsperson or homesteading type work have some similarities.

The Homesteader within the American Mythos

Farmers and small landowners in general have been largely lionized in American history, where examples abound of political figures extolling the virtues, necessity of, and unique individualism belonging to farmers. I’ll admit it’s a little flattering when people talk about the sort of work I did for so long as uniquely virtuous, but I’m left feeling unsure as to how healthy it is for a society to degrade some types of work in order to raise up others. For an example, think of William Jennings Bryan, an American politician popular among farmers in the late 19th century and after its turn. He had a large effect on the views of many rural Americans and regularly espoused the idea that agrarian work was inherently superior to other forms of labor. The classic example of his views is his famous “Cross of Gold” speech, where he said the following:

“You come to us and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard. I tell you that the great cities rest upon these broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic. But destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.”

William Jennings Bryan: “Cross of Gold” July 9, 1896, Chicago

The idea expressed here is clear – farms power the existence of the cities, so they should be shown more respect.

Stepping back another century, think of Thomas Jefferson. He was arguably the primary supporter for the United States to be an agrarian republic during its founding, through his writings such as “Notes on the State of Virginia.” In mentioning this book, I must note that many viewpoints he expresses in it are clearly and deeply reprehensible, primarily his comments on race, and those on the law. Still, the views of Jefferson were advanced by many in the early days of the United States and he influenced much of the national consciousness, regardless of my opinion on him. Richard Hofstadter, an American historian has written thoroughly on the subject of this phenomenon and its impact on American values. His work includes much discussion of the social establishment of virtues in the United States around agrarianism, with one example being his essay “The Myth of the Happy Yeoman.” In it, he gives an excellent and concise description of the manner in which people such as Jefferson or Bryan argued about the superiority of rural life:

“Like any complex of ideas, the agrarian myth cannot be defined in a phrase, but its component themes form a clear pattern. Its hero was the yeoman farmer, its central conception the notion that he is the ideal man and the ideal citizen. Unstinted praise of the special virtues of the farmer and the special values of rural life was coupled with the assertion that agriculture, as a calling uniquely productive and uniquely important to society, had a special right to the concern and protection of government. The yeoman, who owned a small farm and worked it with the aid of his family, was the incarnation of the simple, honest, independent, healthy, happy human being. Because he lived in close communion with beneficent nature, his life was believed to have a wholesomeness and integrity impossible for the depraved populations of cities.”

Richard Hofstadter: “The Myth of the Happy Yeoman”, 1956

To me, this feels almost as if it could have been written today, in description aimed towards the varying videos and posts on social media waxing poetically on the forgotten idyllic lifestyles of life on the farm. Yet this was written almost seventy years ago, about topics which were in heavy discussion more than fifty years prior. Hofstadter even seems to imply in the essay that this ideal of the yeoman had declined, and says that “agrarian myth” was subsumed and replaced by an “even stronger ideal, the notion of opportunity, of career, of the self-made man.” If the agrarian myth declined and was subsumed, why does it seem to be re-energized today? The key here is the ideal of the self-made man, which brings our focus back to the present day. Though I think the feelings of ennui expressed by many tech workers that inspired me to write this are most pronounced in the field of programming, I don’t think they are limited solely to them.

Psychological Shifts in American Ideals

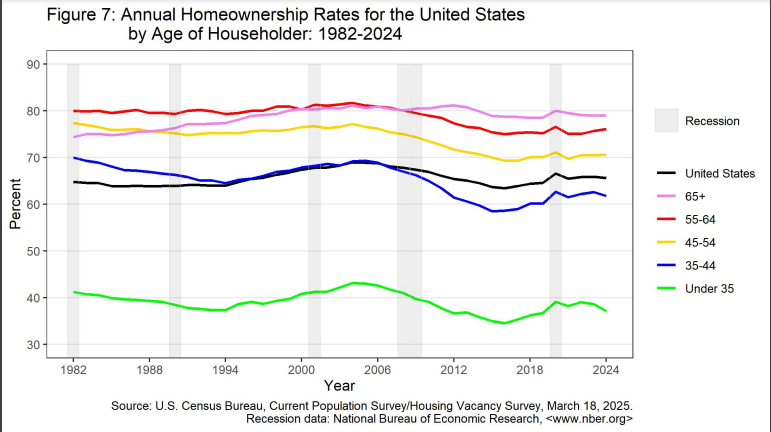

My general opinion is that the ideal of the “self-made man” has made a transition from a widely accepted goal to one viewed as contentious, and to many, unrealistic. The average American citizen no longer views stability in this way as a plausible concept, disheartened by rising income inequality and disillusioned by the proliferation of easily accessed get-rich-quick schemes (with obviously low rates of success) such as cryptocurrency, app-based stock trading within meme stocks, and exploitation of audiences by sudden social media stars. These feelings of despair often center around the idea of homeownership – central to the ideal of the yeoman and of any independent citizen is the idea of owning a residence, and of setting roots in an area. Whether or not owning housing is as achievable as it was in the past in the US is a complicated question – the rate of increase in housing costs has been significantly higher than the rate of increase in average wage over the last 60 years, so housing is unarguably taking up a larger percentage of our income. Though data prior to 1980 on homeownership by age group is harder to come by, it appears that it has not changed dramatically for most groups (the main difference being a slight downward trend and a significant drop during and after the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis for most groups which are not older than age 65, while the 65+ group has over time increased their homeownership rates by about 5%).

One could argue, as many have, that some of this increase in housing cost is offset by decreased costs in other expenditures such as food or technology. However, the important point here is not about whether the material reality has effectively changed, but in how individuals currently perceive both the current reality and the past. As recently as two years ago, Americans polled on whether they believe that life for people like now compared to 50 years ago was better or worse generally said that they believed life was now worse. There is a pervasive belief that life was better in the past and I believe that individuals who feel this way tend to move themselves towards social values that they see as indicative of the past, such as agrarian lifestyles. They retreat to an earlier part of the American psyche, to that of the independent farmer, escaping from the confusion and fear they see in a modern economy and impersonality of technology.

One counterpoint to this is as follows – if this is prevalent in individuals employed in tech, could it truly be linked to income inequality? Many tech workers enjoy high incomes relative to the average worker in this country. This is true, but it draws us to our next point, that of alienation. This is a topic which is less grounded in surveys or statistics, but one which is more readily understood simply through discussion of how we view the nature of work. Many individuals find satisfaction from being appreciated for what they contribute in their work, a simple enough proposition. However, direct service and interaction with the individuals who benefit from your work is generally not an efficiency within a market. One baker making bread for his neighbors may find more satisfaction in that, but wouldn’t it be more efficient to have a centralized bread distribution factory, staffed by hundreds of bakers, who have their pooled effort in the form of hearty loaves of glutenous manna distributed efficiently across multiple communities? As we create more and more efficient economies across a variety of fields of work, we continually disentangle and alienate individuals from the effects and recipients of their labor. When you become detached from the meaning behind your work in this way though, it becomes difficult to assign meaning to your work.

It is difficult to think of any field more forcibly disentangled from any sort of understanding of the impact of your labor than the majority of positions in tech. Through a series of entirely digital processes you are completing tasks which often, upon reflection, feel almost imaginary. Programs pushed through layers of committees work well to distribute responsibility for potential bugs or issues, but they have a secondary effect of stripping much of the individual ownership of a given product. If you were some engineer working on a large corporate website, it’s less that you made the whole experience, and more that you contributed to it. You likely never see any indication of whether people appreciate or like the things that you made beyond abstract visit rates and click-through statistics, as opposed to a person acknowledging that you created something that they appreciate. Of course people in this position would feel deeply alienated from the work that they do over time, even when they logically understand the economic or personal value of what they create, the emotional connection they seek to find value through work is lacking. This is exactly where it ties back into the rising income inequality though – say you’re a programmer working at a company that you feel is draining your soul. You feel no connection to your work. But what else can you do? You’re fully aware that other careers pay far less, so why would you work in a different position, especially when you’ve already worked your way up the ladder within this one? This choice could feel even worse if you had a family depending on you. So instead many people detach, they start to feel more apathetic and they simply step through the motions. Some others instead start to yearn to turn back the clock to an almost mythical time period that they see depicted in popular media as better. It is exactly this combination of alienation from the meaning of one’s labor, a lack of confidence in the viability of a stable career-driven path to “success” or becoming “self-made” without luck, and a view of craft-based or agricultural labor as existing in a different time period possessing greater intrinsic meaning and inherent nobility which combine together within the American psyche to form a fascination with these types of work across social strata. Idealization of farming seems much more likely now that it almost feels mythical as compared to when most individuals likely either were engaged in it or knew someone who was.

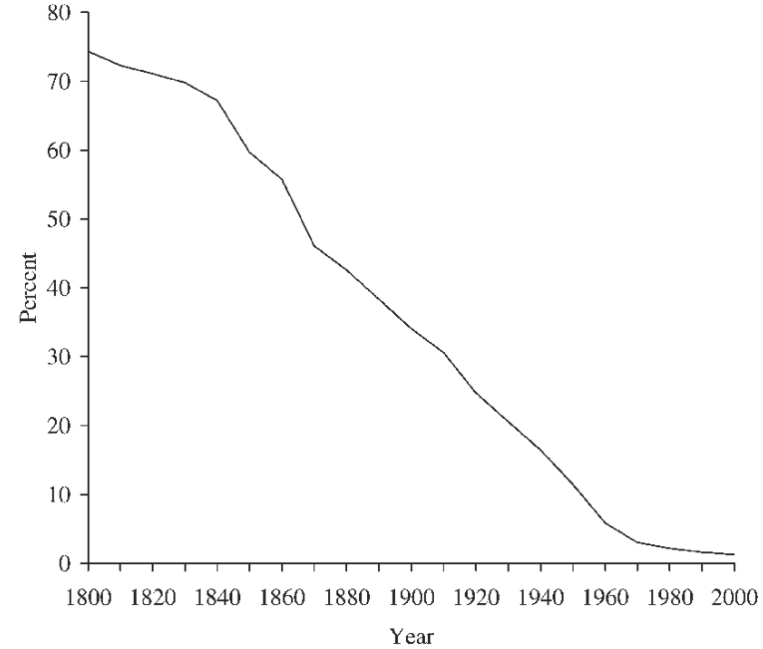

Image: Percent of the Labor Force Employed in Agriculture, United States, 1800 to 2000. Source: Ruggles, Steven. (2007). The Decline of Intergenerational Coresidence in the United States, 1850 to 2000. American sociological review. 72. 964-989. 10.1177/000312240707200606.

In the above chart, Dr. Ruggles demonstrates as part of his paper on the decline of intergenerational coresidence in the US the astronomical change in the amount of agricultural workers in the country, dropping from it being the occupation of the vast majority of the labor force to only a tiny percent over the last few decades. Importantly, there is now no American alive who remembers the country when more than a 20%-30% of its workers were employed in agriculture. The median American by age, in their late 30s currently, has only ever known a world where a single-digit proportion of the US workforce was working agriculturally.

In fact, given these statistics I would take the point of these sort of agrarian type jobs seeming mythical a step further, given that so few Americans are familiar with the actual work behind jobs in the agricultural sector or related ones, I would argue that for many Americans the reality of this type of work is almost indistinguishable from fables or myth in their psychological context, due to lack of exposure. Due to that seeming separation from their mental context of what work is, it enhances the feeling of escapism which this work-fantasy provides, though the conception many hold of it is even more accurately described as a fable due to the significant difference between reality and the projection which many seem to aim for in their cottagecore fantasy. Certainly on Instagram or TikTok you can find depictions of women waltzing through their gardens, baby in their arms, cheery-faced while their husband walks around with flannel and chops wood and their goats bleat in the distance and a chicken pecks in the yard. This idyllic view certainly leaves out the part where she has to take a pick and scrape dirt and feces out of those goats hooves and trim them on a regular basis to prevent foot-rot (They certainly didn’t evolve to walk in dirt all day, but to jump around on rocks). It doesn’t touch on when they hadn’t realized that they had too high a rooster hen ratio, and woke up to find one rooster pulling the eyes of another one out of its skull. It certainly doesn’t display the economic difficulties inherent in these agricultural endeavors: checking your fruit trees and seeing half your apples have one large bite out of them from deer, looking in your coop and seeing that several of your hens got dragged off by foxes or coyotes, having one of your prime dairy cows die due to complications after a stillbirth, going to water your large tomato crop and finding that blister beetles have started stripping all the foliage from your plants. The possibilities are endless and the situations are often dirty and difficult, and while for a hobby farm these are just unfortunate setbacks, if your ability to put food on the table for your family is determined by the outcome of these sort of situations, then they’re less of a setback and more of a devastating blow to whether or not you can remain economically solvent.

The idealization of farmers and craftsmen is not unique to the USA either(see Tolstoy’s opinions on agrarianism as well), but I can primarily speak to how people feel about the current climate of work within our country. I will say that I think many people yearning to turn back many changes in society are largely misguided in this – though there is absolutely value in hands on work, in serving one’s community, turning back the clock in all aspects risks erasing so many true gains we’ve made as a society, especially if the core of the issue is in our relationship with work as a society. Personally, I can’t deny that seeing someone doing work with their own two hands feels more authentic and true to me. I find the idea of others in my field who have never experienced physical labor very strange to consider. There is a clear flaw with some of this idealization though. The ideal of finding our value in work and making something of ourselves through the sweat of our brow is a noble one in many ways but contains a corrosive core as well. If you center your value entirely in how appreciative others are of the contributions you make, and in what you can provide, you ignore the actual concept of community, and you potentially build a worldview that denigrates those who you view as not contributing “enough” in your manner. This is purely my opinion, but I think the healthier way to approach this concept is one of sacrifice and service. If you have the capability to contribute work in some way – physical strength, knowledge, or mental acuity, then you have a moral responsibility to do so – yet not having as much capability as some other person is not something that should negate your self-worth. Instead, the act of doing what you can is what should be seen as virtuous, rather than the absolute economic output of your personal capability. Do what you can, build a community through simple acts of socialization and giving to others, and improve the lives of everyone around you. That is how we find fulfillment in a world such as this one.

Theodore Morley